Wednesday, July 19. A few days since, Mr. John Stuart and company, came here, from New Caledonia, for goods; and to day, they set out on their return home. During the few days which that gentleman passed here, I derived much satisfaction from his society. We rambled about the plains, conversing as we went, and now and then stopping, to eat a few berries, which are every where to be found. He has evidently read and reflected much. How happy should I be to have such a companion, during the whole summer. But such is our mode of life in this country, that we meet but seldom; and the time that we remain together, is short. We only begin to find the ties of friendship, binding us closely together, when we are compelled to separate, not to meet again perhaps for years to come. Baptiste La Fleur, my interpreter, will accompany Mr. Stuart and his men, as far as St. John's, in hopes of obtaining some information respecting his brother, who, it is supposed, was killed by an Indian, the last spring, while on his way from the Rocky Mountain Portage to St. John's.

Tuesday, 22. Messrs. J. Stuart, and H. Faries and company, passed this place in four canoes, with the returns of New Caledonia and Rocky Mountain Portage; and, .like many others, they are on their way to the Rainy Lake.

Saturday, October 6. Mr. John Stuart and company, in four canoes, have arrived from Fort Chippewyan, having on board, goods for the establishment at the Rocky Mountain Portage and New Caledonia. This gentleman delivered me a packet of letters from home, and also a number of others from gentlemen in this country, one of which is a joint letter, signed by three of the partners, requesting me to go and superintend the affairs of New Caledonia; or, if I prefer it, to accompany Mr. Stuart, as second in command to him, until the next spring, at which time it is presumed, that I shall have learned sufficient of the state of things in that country, to assume the whole management myself. As Mr. Stuart has passed several years in that part of the country, the information which his experience will enable him to afford me, will be of great service. I prefer, therefore, accompanying him, to going alone, especially in view of the late unfavourable reports from that country, in regard to the means of subsistence.

Wednesday, October 10. St. John's. On the 7th Mr. Stuart and myself, with our company, left Dunvegan; and this evening, we arrived here. The current in the river begins to be much stronger than we found it below Dunvegan. On both sides of the river, are hills of a considerable height, which are almost destitute of timber of any kind. At different places, we saw buffaloes, red deer, and bears. During our passage to this place, the weather has been bad. The snow and rain have been very unpleasant, unprotected against them, as we are, in our open canoes. Thursday, 11. In the early part of the day, our people were busily employed in preparing Portage. Having a little business still to transact, I shall pass the night here.

Monday, 15. Rocky Mountain Portage Fort. We here find nearly eight inches of snow. Mr. Stuart and company reached here yesterday; and I arrived this morning. Be tween this place and St. John's, the river is very rapid, its banks are high, and the country, on both sides of it, is generally clothed with small timber. Ever since our arrival, we have been employed in delivering goods for this place, and dividing the remainder among our people, to be taken on their backs, to the other end of the portage, which is twelve miles over, through a rough and hilly country. We leave our canoes and take others, at the other end of the carrying place.

Wednesday, 14. The lake, opposite to the fort, froze over the last night. To day Mr. Stuart and company, arrived from McLeod's Lake. Saturday, 17. We have now about eight inches of snow on the ground. Sunday, 18. Mr. Stuart and company, have gone to Frazer's Lake. I accompanied them to the other side of this lake, where I saw all the Indians belonging to the village in this vicinity. They amount to about one hundred souls, are very poorly clothed, and, to us, appear to be in wretched circumstances; but they are, notwithstanding, contented and cheerful.

Friday, November 6. We have now about six inches of snow on the ground.—On the 27th ult. I set out for McLeod's Lake, where I arrived on the 29th. I there found Mr. John Stuart, who, with his company, arrived the day before, from Fort Chipewyan. His men are on their way to the Columbia River, down which they will proceed under Mr. J. G. McTavish. The coming winter, they will pass near the source of that river. At the Pacific Ocean, it is expected that they will meet Donald McTavish, Esq., and company, who were to sail from England, last October, and proceed round Cape Horn to the mouth of Columbia River. This afternoon Mr. Stuart and myself, with our company, arrived at this place, (Stuart's Lake) where both of us, God willing, shall pass the ensuing winter. With us, are twenty-one labouring men, one interpreter, and five women, besides children.

Saturday, January 23, 1813. On the 29th ult. Mr. Stuart and myself, with the most of our people, went to purchase furs and salmon, at Frazer's Lake and Stillas. The last fall, but few salmon came up this river. At the two places, above mentioned, we were so successful as to be able to procure a sufficient quantity. While at Frazer's Lake Mr. Stuart, our interpreter and myself, came near being massacred by the Indians of that place, on account of the interpreter's wife, who is a native of that village. Eighty or ninety of the Indians armed themselves, some with guns, some with bows and arrows, and others with axes and clubs, for the purpose of attacking us. By mild measures, however, which I have generally found to be the best, in the management of the Indians, we succeeded in appeasing their anger, so that we suffered no injury; and we finally separated, to appearance, as good friends, as if nothing unpleasant had occurred. Those who are acquainted with the disposition of the Indians and who are a little respected by them, may, by humouring their feelings, generally, control them, almost as they please.

Saturday, 25. An Indian has arrived, from a considerable distance down this river, who has delivered to me three letters from Mr. J. Stuart. The last of them is dated at O-kena-gun Lake, which is situated at a short distance from the Columbia River. Mr. Stuart writes, that he met with every kindness and assistance from the Natives, on his way to that place; that, after descending this river, during eight days, he was under the necessity of leaving his canoes, and of taking his property on horses, more than one hundred and fifty miles, to the above mentioned Lake. From that place, he states, that they can go all the way by water, to the Ocean, by making a few portages; and he hopes to reach the Pacific Ocean, in twelve or fifteen days, at farthest. They will be delayed, for a time, where they are, by the necessary construction of canoes.

Sunday, November 7. This afternoon, Mr. Joseph La Roque and company arrived from the Columbia River. This gentleman went, the last summer, with Mr. J. G. McTavish and his party, to the Pacific Ocean. On their return, they met Mr. Stuart and his company. Mr. La Roque, accompanied by two of Mr. Stuart's men, set off thence, to come to this place, by the circuitous way of Red Deer River, Lesser Slave Lake, and Dun vegan, from which last place, they were accompanied by my people, who have been, this summer, to the Rainy Lake. By them I have received a number of letters from people in this country, and from my friends in the United States.

Friday, February 4. This evening, Mr. Donald McLeunen and company, arrived here from the Columbia Department, with a packet of letters. One of these is from Mr. John Stuart, informing me that the last autumn, the North West Company purchased of the Pacific Fur Company, all the furs which they had bought of the Natives, and all the goods which they had on hand. The people who were engaged in the service of that company, are to have a passage, the next summer, to Montreal, in the canoes of the North West Company, unless they choose to enter into our service.

Saturday, 29. My people have returned from the Rainy Lake, and delivered me letters from my relatives below. They afford me renewed proof of the uncertainty of earthly objects and enjoyments, in the intelligence, that a brother's wife has been cut down by death, in the midst of her days, leaving a disconsolate husband, and two that the rest of my numerous relatives, are blessed with health, and a reasonable portion of earthly comforts. I have also received a letter from Mr. John Stuart, who has arrived at McLeod's Lake, desiring me to go and superintend the affairs at Frazer's Lake, and to send Mr. La Roque, with several of the people who are there, to this place, that they may return to the Columbia department, where it is presumed they will be more wanted, than in this quarter. Tomorrow, therefore, I shall depart for Frazer's Lake.

Monday, 27. The weather is serene and cold; and thus far, this has been much the coldest winter that I have experienced in this part of the country.—The winters are, generally milder here, than in most parts of - the North West. Mr. Stuart has just left me, on his return home. The few days which he has spent here, were passed much to our mutual satisfaction; and I hope that we shall reap some benefit from this visit. Religion was the principal topic, on which we conversed, because, to both of us, it was more interesting than any other. Indeed, what ought to interest us so much, as that which concerns our eternal welfare? I, at times, almost envy the satisfaction of those, who live among christian people, with whom they can converse, at pleasure, on the great things of religion, as it must be a source of much satisfaction, and of great advantage, to a pious mind.

Monday, July 24. , Fruits, of various kinds, now begin to ripen. Of this delicious food, the present prospect is, that we shall soon have an abundance; and for this favour, it becomes us to be grateful to the Bestower. The person who is surrounded with the comforts of civilized life,- knows not how we prize these delicacies of the wilderness. Our circumstances, also, teach us to enjoy and to value the intercourse of friendship. To be connected, and to have intercourse, with a warm and disinterested friend, who is able, and will be faithful, to point out our faults, and to direct us by his good counsel, is surely a great blessing. Such a friend, I have, in my nearest neighbour, Mr. Stuart. For some time past, he has frequently written to me long, entertaining and instructive letters, which are a cordial to my spirits, too often dejected, by the loneliness of my situation, and more frequently, by reflections on my past life of folly and of sin. Mr. James McDougall, also, another gentleman in this department, is equally dear to me. His distance from me, renders intercourse less practicable; but endeavour to make up in conversation, for our long separation.

Monday, April 15. My desire to return to my native country has never been so intense, since I took up my abode in the wilderness, as it is now, in consequence of the peculiar situation of my friends; yet, I cannot think of doing it this season, as it is absolutely necessary that I should pass the ensuing summer at this place. I shall write to my friends below, a few days hence; and as we live in a world of disappointment and death, I am resolved to forward to them by Mr. John Stuart, a copy of my Journal, in order that they may know something of the manner in which I have been employed, both as it respects my temporal and spiritual concerns, while in the wilderness, if I should never enjoy the inexpressible pleasure of a personal intercourse with them.

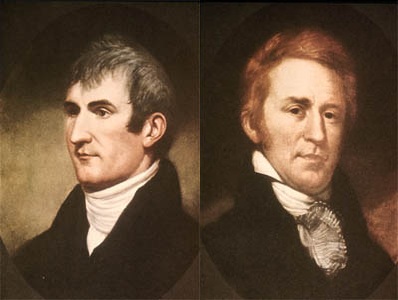

See Wikipedia entry for John Stuart (explorer)

The Life, times, and travels of NorthWest Company fur trader Lisette Laval Harmon (1798-1863) and of heritage interpreter Lynn Noel, following in her footsteps since 1988 through living history and experiential education

Map

Timeline

Sunday, March 22, 2015

In Daniel's Words: William Henry

Thursday, 29. On the 22nd instant, Mr. McLeod, with ten of his people, arrived on horseback; and on the day following, I accompanied them to the lowef fort, where I met Mr. William Henry, a clerk. Mr. McLeod has also brought another clerk into this country, by the name of Frederick Goedike. This evening, Messrs. McLeod, Henry and myself returned, but left the people behind, whose horses are loaded with goods, for this place and Alexandria.

Sunday, 23. It has snowed all day; and about six inches have fallen. I am waiting the arrival of Mr. Henry to take charge of this post, when I shall proceed to Alexandria.

Sunday, 4. Mr. William Henry and company arrived from the Bird Mountain, and inform us, that they are destitute of provision there. They will, therefore, come and pass the remainder of the summer with us; for we now have provisions in plenty.

Thursday, January 27, 1803. I have just returned from Alexandria, where I passed six days, much to my satisfaction, in the company of Messrs. H. McGillies, W. Henry and F. Goedike. While there, I wrote to Messrs. McLeod, A. Henry and J. Clarke, all of Athabasca, which letters will be taken to them, by our winter express.

Tuesday, December 27. Messrs. Henry and Goedike, my companions and friends, are both absent, on excursions into two different parts of the country. I sensibly feel the loss of their society, and pass, occasionally, a solitary hour, which would glide away imperceptibly, in their company. When they are absent I spend the greater part of my time in reading and writing.

Tuesday, 6. North side of the Great Devil's Lake, or as the Natives call it, Much e-man-e-to Sa-ky-e-gun. As I had nothing of importance to attend to, while our people would be absent in their trip to and from the fort, and was desirous of seeing my friend Henry, who, I understood, was about half a day's march from where I was the last night, I therefore, set off this morning, accompanied by an Indian lad who serves as a guide, with the intention of visiting this place.

Wednesday, 7. Canadian's Camp. This place is so called from the fact, that a number of our people have passed the greater part of the winter here. As there is a good foot path, from the place where I slept last night to this place, I left my young guide and came here alone. Frequently on the way, I met Indians, who are going to join those at the Devil's Lake. I came here in the pleasing expectation of seeing my friend Henry; but I am disappointed. Yesterday morning, he set out for Alexandria. I hope to have the satisfaction, however, of soon meeting him at the fort.

Sunday, 29. Yesterday, the greater part of our people set out for Swan River; and to day, Mr. McGillies, and the most of those who were left, have departed for the New Fort, which is distant about forty-five miles, to the north west from the former general rendezvous, the Grand Portage, which the Americans have obliged us to abandon. It is thought necessary that I should pass another summer at this place; but I am happy in having with me my friends Henry and Goedike. There are here also one interpreter and several labouring men, besides women and children.

Monday, August 1. Lake Winnipick. This morning, we arrived at the fort on this lake, where we remained until noon. While there, I wrote to my old friend Mr. William Henry, who is at the Lower Red River. I also received a letter from him, in which he informs me, that his fort was attacked this summer, by a considerable party of Sieux. Two shots, from cannon in the block houses, however, caused them to retire, in doing which, they threatened that they would before long, return and make another attempt to take the fort.

Sunday, 23. It has snowed all day; and about six inches have fallen. I am waiting the arrival of Mr. Henry to take charge of this post, when I shall proceed to Alexandria.

Sunday, 4. Mr. William Henry and company arrived from the Bird Mountain, and inform us, that they are destitute of provision there. They will, therefore, come and pass the remainder of the summer with us; for we now have provisions in plenty.

Thursday, January 27, 1803. I have just returned from Alexandria, where I passed six days, much to my satisfaction, in the company of Messrs. H. McGillies, W. Henry and F. Goedike. While there, I wrote to Messrs. McLeod, A. Henry and J. Clarke, all of Athabasca, which letters will be taken to them, by our winter express.

Tuesday, December 27. Messrs. Henry and Goedike, my companions and friends, are both absent, on excursions into two different parts of the country. I sensibly feel the loss of their society, and pass, occasionally, a solitary hour, which would glide away imperceptibly, in their company. When they are absent I spend the greater part of my time in reading and writing.

Tuesday, 6. North side of the Great Devil's Lake, or as the Natives call it, Much e-man-e-to Sa-ky-e-gun. As I had nothing of importance to attend to, while our people would be absent in their trip to and from the fort, and was desirous of seeing my friend Henry, who, I understood, was about half a day's march from where I was the last night, I therefore, set off this morning, accompanied by an Indian lad who serves as a guide, with the intention of visiting this place.

Wednesday, 7. Canadian's Camp. This place is so called from the fact, that a number of our people have passed the greater part of the winter here. As there is a good foot path, from the place where I slept last night to this place, I left my young guide and came here alone. Frequently on the way, I met Indians, who are going to join those at the Devil's Lake. I came here in the pleasing expectation of seeing my friend Henry; but I am disappointed. Yesterday morning, he set out for Alexandria. I hope to have the satisfaction, however, of soon meeting him at the fort.

Sunday, 29. Yesterday, the greater part of our people set out for Swan River; and to day, Mr. McGillies, and the most of those who were left, have departed for the New Fort, which is distant about forty-five miles, to the north west from the former general rendezvous, the Grand Portage, which the Americans have obliged us to abandon. It is thought necessary that I should pass another summer at this place; but I am happy in having with me my friends Henry and Goedike. There are here also one interpreter and several labouring men, besides women and children.

Monday, August 1. Lake Winnipick. This morning, we arrived at the fort on this lake, where we remained until noon. While there, I wrote to my old friend Mr. William Henry, who is at the Lower Red River. I also received a letter from him, in which he informs me, that his fort was attacked this summer, by a considerable party of Sieux. Two shots, from cannon in the block houses, however, caused them to retire, in doing which, they threatened that they would before long, return and make another attempt to take the fort.

Saturday, March 21, 2015

In Daniel's Words: Frederick Goedike

Thursday, 29. On the 22nd instant, Mr. McLeod, with ten of his people, arrived on horseback; and on the day following, I accompanied them to the lower fort, where I met Mr. William Henry, a clerk. Mr. McLeod has also brought another clerk into this country, by the name of Frederick Goedike. This evening, Messrs. McLeod, Henry and myself returned, but left the people behind, whose horses are loaded with goods, for this place and Alexandria.

Monday, 31. Alexandria. ... Mr. Goedike is to pass the summer with me, also two interpreters, and three labouring men, besides several women and children, who together, form a snug family.

Thursday, January 27, 1803. I have just returned from Alexandria, where I passed six days, much to my satisfaction, in the company of Messrs. H. McGillies, W. Henry and F. Goedike. While there, I wrote to Messrs. McLeod, A. Henry and J. Clarke, all of Athabasca, which letters will be taken to them, by our winter express.

Wednesday, May 4. Alexandria. Here, if Providence permit, I shall pass another summer, and have with me Mr. F. Goedike, one interpreter and several labouring men, besides women and children. As Mr. Goedike will be absent from the fort, during the greater part of the summer, I shall be, in a great measure, alone; for ignorant Canadians furnish little society. Happily for me, I have lifeless friends, my books, that will never abandon me, until I first neglect them.

Tuesday, 21. This afternoon, we had an uncommonly heavy shower of hail and rain. Yesterday, I sent Mr. F. Goedike, accompanied by several of our people, with a small assortment of goods, to remain at some distance from this, for several weeks. In the absence of my friend, this is to me, a solitary place. At such times as this, my thoughts visit the land of my nativity; and I almost regret having left my friends and relatives, among whom I might now have been pleasantly situated, but for a roving disposition. But Providence, which is concerned in all the affairs of men, has, though unseen, directed my way into this wilderness; and it becomes me to bear up under my circumstances, with resignation, perseverance and fortitude. I am not forbidden to hope, that I shall one day enjoy, with increased satisfaction, the society of those friends, from whom I have for a season banished myself.

Tuesday, December 27. Messrs. Henry and Goedike, my companions and friends, are both absent, on excursions into two different parts of the country. I sensibly feel the loss of their society, and pass, occasionally, a solitary hour, which would glide away imperceptibly, in their company.

Saturday, 24. Yesterday, Mr. F. Goedike arrived from Alexandria, and delivered me a letter from Mr. McGillies, requesting me to abandon Lac la Peche, and proceed, with all my people, to Alexandria. In the fore part of the day, we all left the former place.

Sunday, 29. Yesterday, the greater part of our people set out for Swan River; and to day, Mr. McGillies, and the most of those who were left, have departed for the New Fort, which is distant about forty-five miles, to the north west from the former general rendezvous, the Grand Portage, which the Americans have obliged us to abandon. It is thought necessary that I should pass another summer at this place; but I am happy in having with me my friends Henry and Goedike. There are here also one interpreter and several labouring men, besides women and children. We are preparing a piece of ground for a garden, the cultivation of which, will be an amusement; and the produce of it, we hope, will add to our comforts. Mr. Goedike plays the violin, and will occasionally cheer our spirits, with an air. But the most of our leisure time, which is at least five sixths of the whole, will be spent in reading, and in meditating and conversing upon what we read. How valuable is the art, which multiplies books, with great facility, and at a moderate expense. Without them the wheels of time would drag heavily, in this wilderness.

Thursday, 31. In the morning, Mr. Goedike, Collin, my interpreter, a young lad and myself, set off for the purpose of paying a visit to our X. Y. neighbours. On leaving the fort, we had the river to cross, which, in consequence of the late rains, is about sixty rods broad. Our only means of crossing it was a canoe, made of the skins of buffaloes, which, on account of the length of time that it had been in the water, began to be rotten. Before we reached the other side of the river, the canoe was nearly half Hilled with water. We drew it on shore, mounted our horses, visited our neighbours, and returned to the place where we had left our canoe, at about three o'clock P. M. Having repaired it a little, we embarked, for the purpose of returning to the fort. We soon perceived that the water came into the canoe very fast; and we continued paddling, in hope of reaching the opposite shore, before it would fill. We were, however, sadly disappointed; for it became full, when we had gone about one third of the distance; but it did not immediately overset. The water, in that place, was about five feet deep; but the current was strong, and it soon carried us to a place where we could not reach the bottom, and the canoe overset. We all clung to it and, thus drifted a considerable distance, until the canoe was, at length, stopped by a few willows, whose tops rose above the water. Here I had a moment, in which I could reflect on our truly deplorable condition, and directed my thoughts to the means of relief. My first object was, if possible, to gain the shore, in order to free myself from my clothes, which I could not do where I then was. But my great coat, a heavy poniard, boots, &c. rendered it very difficult for me to swim; and I had become so torpid, in consequence of having been so long in the cold water, that before I had proceeded one third of the way to the shore, I sunk, but soon arose again, to the surface of the water. I then exerted myself to the utmost; but, notwithstanding, soon sunk a second time. I now considered that I must inevitably drown; the objects of the world retire from my view, and my mind was intent only upon approaching death; yet I was not afraid to meet my dissolution.* I however made a few struggles more, which happily took me to a small tree that stood on what is usually the bank of the river, but which is now some rods distant from dry land. I remained there for some time, to recover strength, and at length proceeded to the shore; and as soon as I had gained it, my mind rose in ardent gratitude to my gracious Preserver and deliverer, who had snatched me from the very jaws of death! / was now safe on shore; but the condition of my unfortunate companions, was far different. They had still hold of the canoe in the middle of the river, and by struggling were just able to keep themselves from sinking. We had no other craft, with which to go upon the water, nor could any of our people swim, who were standing on the shore, the melancholy spectators of this scene of distress. I therefore took off my clothes, and threw myself, a second time, into the water, in order, if possible, to afford some aid to my companions. When I had reached the place where they were, I directed the boy, to take hold of the hair of my head, and I took him to a staddle, at no great distance, and directed him to lay fast hold of it, by which means he would be able to keep the greater part of his body above water. I then returned to the canoe, and took Collin to-a similar place. Mr. Goedike had alone proceeded to a small staddle, and would have reached the shore, had not the cramp seized him in one of his legs. I next tried to take the canoe ashore, but could not alone effect it. I therefore, swam to the opposite shore, caught a horse and mounted him, and made him swim to the canoe, at one end of which I tied a cord, and taking the other end in my teeth and hands, after drifting a considerable distance, I reached the land. After repairing the canoe a little, I proceeded to my three wretched fellow creatures, who had, by this time, become nearly lifeless, having been in the water at least two hours. By the aid of a kind Providence, however, they at last safely reached the shore; and so deeply were they affected with their unexpected escape, that they prostrated themselves to the earth, in an act of thanksgiving, to their great and merciful Deliverer.

*For at that time, I was Ignorant of my lost condition by nature, and of the necessity of being clothed in a better righteousness than my own, to prepare me to appear with safety before a holy God, in judgment.

Tuesday, 17. On the 8th instant, some Indians ran away with three of our horses; and on the following morning, Mr. Goedike and myself mounted two others, to pursue the thieves. We followed them for two days, and then, ascertaining that they were so far in advance of us, and travelled so fast, that it would be impossible to overtake them, before they would reach their camp, which is six or seven days' march from this, we ceased following them. We directed our course another way, for the purpose of finding buffaloe, but without success. We, however, killed as many fowls, in the small lakes, as we needed for daily consumption; and this evening returned to the fort, having had on the whole a pleasant ride.

Friday, 26. Agreeably to the instructions of Mr. Chaboillez, in company with Mr. La Rocque, and an Indian, who served as guide, I set out on the 6th instant, for Montague a la Basse. Our course was nearly south, over a plain country; and on the 9th, we reached Riviere qui Apelle, where the North West and X. Y. companies have each a fort, where we tarried all night, with Monsieur Poitras, who has charge of that post. The next morning, we continued our march, which was always in beautiful plains, until the 11th, when we arrived at the place of our destination. There I found Mr. Chaboillez, C. McKenzie, &c. The fort is well built, and beautifully situated, on a very high bank of the Red River, and overlooks the country round to a great extent, which is a perfect plain. There can be seen, at almost all seasons of the year, from the fort gate, as I am informed, buffaloes grazing, or antelopes bounding over the extensive plains, which cannot fail to render the situation highly pleasant. I spent my time there very pleasantly, during eight days, in company with the gentlemen above mentioned. At times, we would mount our horses, and ride out into the plains, and frequently try the speed of our beasts. On the 19th, I left that enchanting abode, in company with Messrs. Chaboillez, McKenzie, &c., and the day following, arrived at Riviere qui Apelle, where we found the people, waiting our arrival. They came here by water; but at this season, canoes go up no further, on account of the shallowness of the river. The goods intended for Alexandria, therefore, must be taken from this on horse back. Accordingly, we delivered out to the people such articles as we thought necessary, and sent them 'off; and the day following, Mr. Chaboillez returned to Montagne a la Basse, and Mr. McKenzie and myself proceeded to Alexandria, where we arrived this afternoon, after having made a pleasant jaunt of twenty one days. Here I shall pass the winter, having with me Mr. Goedike, two interpreters, twenty labouring men, fourteen women and sixteen children.

Tuesday, January 21, 1805. For nearly a month, we have subsisted on little besides potatoes; but thanks to a kind Providence, the last night, two of my men returned from the plains, with their sledges loaded with the flesh of the buffaloe. They bring us the pleasing intelligence, that there is a plenty of these animals within a day's march of us. This supply of provisions could not have come more opportunely, for our potatoes are almost gone. About a month since, I sent Mr. Goedike, accompanied by ten men, out into the plains, in hopes that they might fall in with the Natives, who would be able to furnish us with food; but we have heard nothing from them, and I cannot conjecture what should have detained them so long, as I did not expect that they would be absent, for more than ten days, from the fort.

Wednesday, 8. Riviere qui Apelle. On the 6th Mr. Goedike and several other persons with myself, left our boats, and proceeded on horse-back. As the fire has passed over the plains, this spring, it was with difficulty that we could find grass, sufficient for the subsistence of our horses.

Friday, 12. The Plain Portage. In the former part of the day, we met, A. N. McLeod, Esq. who is now from the New Fort, on his way back to Athabasca. We went on shore, and took breakfast with him. He has taken with him my friend Mr. F. Goedike, a young man possessed of a good understanding, and a humane and generous heart, who has been with me for four years past, and from whom I could not separate, without regret.

Friday, 14. This morning, my old friend Mr. F. Goedike, whom I have been happy to meet at this place, left us, with his company, for St. Johns, which is about one hundred and twenty miles up this river, where he is to pass the ensuing winter.

Thursday, 11. We, yesterday, sent off eleven canoes, loaded with the returns of this place and of St. John's; and, early this morning, Messrs. D. McTavish, J. G. McTavish, 1 F. Goedike and J. McGillivray, embarked on board of two light canoes, bound for the Rainy Lake and Fort William. But I am to pass the ensuing summer, at this place.—The last winter was, to me, the most agreeable one that I have yet spent in this country. The greatest harmony prevailed among us, the days glided on smoothly, and the winter passed, almost imperceptibly, away.

Monday, 31. Alexandria. ... Mr. Goedike is to pass the summer with me, also two interpreters, and three labouring men, besides several women and children, who together, form a snug family.

Thursday, January 27, 1803. I have just returned from Alexandria, where I passed six days, much to my satisfaction, in the company of Messrs. H. McGillies, W. Henry and F. Goedike. While there, I wrote to Messrs. McLeod, A. Henry and J. Clarke, all of Athabasca, which letters will be taken to them, by our winter express.

Wednesday, May 4. Alexandria. Here, if Providence permit, I shall pass another summer, and have with me Mr. F. Goedike, one interpreter and several labouring men, besides women and children. As Mr. Goedike will be absent from the fort, during the greater part of the summer, I shall be, in a great measure, alone; for ignorant Canadians furnish little society. Happily for me, I have lifeless friends, my books, that will never abandon me, until I first neglect them.

Tuesday, 21. This afternoon, we had an uncommonly heavy shower of hail and rain. Yesterday, I sent Mr. F. Goedike, accompanied by several of our people, with a small assortment of goods, to remain at some distance from this, for several weeks. In the absence of my friend, this is to me, a solitary place. At such times as this, my thoughts visit the land of my nativity; and I almost regret having left my friends and relatives, among whom I might now have been pleasantly situated, but for a roving disposition. But Providence, which is concerned in all the affairs of men, has, though unseen, directed my way into this wilderness; and it becomes me to bear up under my circumstances, with resignation, perseverance and fortitude. I am not forbidden to hope, that I shall one day enjoy, with increased satisfaction, the society of those friends, from whom I have for a season banished myself.

Tuesday, December 27. Messrs. Henry and Goedike, my companions and friends, are both absent, on excursions into two different parts of the country. I sensibly feel the loss of their society, and pass, occasionally, a solitary hour, which would glide away imperceptibly, in their company.

Saturday, 24. Yesterday, Mr. F. Goedike arrived from Alexandria, and delivered me a letter from Mr. McGillies, requesting me to abandon Lac la Peche, and proceed, with all my people, to Alexandria. In the fore part of the day, we all left the former place.

Sunday, 29. Yesterday, the greater part of our people set out for Swan River; and to day, Mr. McGillies, and the most of those who were left, have departed for the New Fort, which is distant about forty-five miles, to the north west from the former general rendezvous, the Grand Portage, which the Americans have obliged us to abandon. It is thought necessary that I should pass another summer at this place; but I am happy in having with me my friends Henry and Goedike. There are here also one interpreter and several labouring men, besides women and children. We are preparing a piece of ground for a garden, the cultivation of which, will be an amusement; and the produce of it, we hope, will add to our comforts. Mr. Goedike plays the violin, and will occasionally cheer our spirits, with an air. But the most of our leisure time, which is at least five sixths of the whole, will be spent in reading, and in meditating and conversing upon what we read. How valuable is the art, which multiplies books, with great facility, and at a moderate expense. Without them the wheels of time would drag heavily, in this wilderness.

Thursday, 31. In the morning, Mr. Goedike, Collin, my interpreter, a young lad and myself, set off for the purpose of paying a visit to our X. Y. neighbours. On leaving the fort, we had the river to cross, which, in consequence of the late rains, is about sixty rods broad. Our only means of crossing it was a canoe, made of the skins of buffaloes, which, on account of the length of time that it had been in the water, began to be rotten. Before we reached the other side of the river, the canoe was nearly half Hilled with water. We drew it on shore, mounted our horses, visited our neighbours, and returned to the place where we had left our canoe, at about three o'clock P. M. Having repaired it a little, we embarked, for the purpose of returning to the fort. We soon perceived that the water came into the canoe very fast; and we continued paddling, in hope of reaching the opposite shore, before it would fill. We were, however, sadly disappointed; for it became full, when we had gone about one third of the distance; but it did not immediately overset. The water, in that place, was about five feet deep; but the current was strong, and it soon carried us to a place where we could not reach the bottom, and the canoe overset. We all clung to it and, thus drifted a considerable distance, until the canoe was, at length, stopped by a few willows, whose tops rose above the water. Here I had a moment, in which I could reflect on our truly deplorable condition, and directed my thoughts to the means of relief. My first object was, if possible, to gain the shore, in order to free myself from my clothes, which I could not do where I then was. But my great coat, a heavy poniard, boots, &c. rendered it very difficult for me to swim; and I had become so torpid, in consequence of having been so long in the cold water, that before I had proceeded one third of the way to the shore, I sunk, but soon arose again, to the surface of the water. I then exerted myself to the utmost; but, notwithstanding, soon sunk a second time. I now considered that I must inevitably drown; the objects of the world retire from my view, and my mind was intent only upon approaching death; yet I was not afraid to meet my dissolution.* I however made a few struggles more, which happily took me to a small tree that stood on what is usually the bank of the river, but which is now some rods distant from dry land. I remained there for some time, to recover strength, and at length proceeded to the shore; and as soon as I had gained it, my mind rose in ardent gratitude to my gracious Preserver and deliverer, who had snatched me from the very jaws of death! / was now safe on shore; but the condition of my unfortunate companions, was far different. They had still hold of the canoe in the middle of the river, and by struggling were just able to keep themselves from sinking. We had no other craft, with which to go upon the water, nor could any of our people swim, who were standing on the shore, the melancholy spectators of this scene of distress. I therefore took off my clothes, and threw myself, a second time, into the water, in order, if possible, to afford some aid to my companions. When I had reached the place where they were, I directed the boy, to take hold of the hair of my head, and I took him to a staddle, at no great distance, and directed him to lay fast hold of it, by which means he would be able to keep the greater part of his body above water. I then returned to the canoe, and took Collin to-a similar place. Mr. Goedike had alone proceeded to a small staddle, and would have reached the shore, had not the cramp seized him in one of his legs. I next tried to take the canoe ashore, but could not alone effect it. I therefore, swam to the opposite shore, caught a horse and mounted him, and made him swim to the canoe, at one end of which I tied a cord, and taking the other end in my teeth and hands, after drifting a considerable distance, I reached the land. After repairing the canoe a little, I proceeded to my three wretched fellow creatures, who had, by this time, become nearly lifeless, having been in the water at least two hours. By the aid of a kind Providence, however, they at last safely reached the shore; and so deeply were they affected with their unexpected escape, that they prostrated themselves to the earth, in an act of thanksgiving, to their great and merciful Deliverer.

*For at that time, I was Ignorant of my lost condition by nature, and of the necessity of being clothed in a better righteousness than my own, to prepare me to appear with safety before a holy God, in judgment.

Tuesday, 17. On the 8th instant, some Indians ran away with three of our horses; and on the following morning, Mr. Goedike and myself mounted two others, to pursue the thieves. We followed them for two days, and then, ascertaining that they were so far in advance of us, and travelled so fast, that it would be impossible to overtake them, before they would reach their camp, which is six or seven days' march from this, we ceased following them. We directed our course another way, for the purpose of finding buffaloe, but without success. We, however, killed as many fowls, in the small lakes, as we needed for daily consumption; and this evening returned to the fort, having had on the whole a pleasant ride.

Friday, 26. Agreeably to the instructions of Mr. Chaboillez, in company with Mr. La Rocque, and an Indian, who served as guide, I set out on the 6th instant, for Montague a la Basse. Our course was nearly south, over a plain country; and on the 9th, we reached Riviere qui Apelle, where the North West and X. Y. companies have each a fort, where we tarried all night, with Monsieur Poitras, who has charge of that post. The next morning, we continued our march, which was always in beautiful plains, until the 11th, when we arrived at the place of our destination. There I found Mr. Chaboillez, C. McKenzie, &c. The fort is well built, and beautifully situated, on a very high bank of the Red River, and overlooks the country round to a great extent, which is a perfect plain. There can be seen, at almost all seasons of the year, from the fort gate, as I am informed, buffaloes grazing, or antelopes bounding over the extensive plains, which cannot fail to render the situation highly pleasant. I spent my time there very pleasantly, during eight days, in company with the gentlemen above mentioned. At times, we would mount our horses, and ride out into the plains, and frequently try the speed of our beasts. On the 19th, I left that enchanting abode, in company with Messrs. Chaboillez, McKenzie, &c., and the day following, arrived at Riviere qui Apelle, where we found the people, waiting our arrival. They came here by water; but at this season, canoes go up no further, on account of the shallowness of the river. The goods intended for Alexandria, therefore, must be taken from this on horse back. Accordingly, we delivered out to the people such articles as we thought necessary, and sent them 'off; and the day following, Mr. Chaboillez returned to Montagne a la Basse, and Mr. McKenzie and myself proceeded to Alexandria, where we arrived this afternoon, after having made a pleasant jaunt of twenty one days. Here I shall pass the winter, having with me Mr. Goedike, two interpreters, twenty labouring men, fourteen women and sixteen children.

Tuesday, January 21, 1805. For nearly a month, we have subsisted on little besides potatoes; but thanks to a kind Providence, the last night, two of my men returned from the plains, with their sledges loaded with the flesh of the buffaloe. They bring us the pleasing intelligence, that there is a plenty of these animals within a day's march of us. This supply of provisions could not have come more opportunely, for our potatoes are almost gone. About a month since, I sent Mr. Goedike, accompanied by ten men, out into the plains, in hopes that they might fall in with the Natives, who would be able to furnish us with food; but we have heard nothing from them, and I cannot conjecture what should have detained them so long, as I did not expect that they would be absent, for more than ten days, from the fort.

Wednesday, 8. Riviere qui Apelle. On the 6th Mr. Goedike and several other persons with myself, left our boats, and proceeded on horse-back. As the fire has passed over the plains, this spring, it was with difficulty that we could find grass, sufficient for the subsistence of our horses.

Friday, 12. The Plain Portage. In the former part of the day, we met, A. N. McLeod, Esq. who is now from the New Fort, on his way back to Athabasca. We went on shore, and took breakfast with him. He has taken with him my friend Mr. F. Goedike, a young man possessed of a good understanding, and a humane and generous heart, who has been with me for four years past, and from whom I could not separate, without regret.

Friday, 14. This morning, my old friend Mr. F. Goedike, whom I have been happy to meet at this place, left us, with his company, for St. Johns, which is about one hundred and twenty miles up this river, where he is to pass the ensuing winter.

Thursday, 11. We, yesterday, sent off eleven canoes, loaded with the returns of this place and of St. John's; and, early this morning, Messrs. D. McTavish, J. G. McTavish, 1 F. Goedike and J. McGillivray, embarked on board of two light canoes, bound for the Rainy Lake and Fort William. But I am to pass the ensuing summer, at this place.—The last winter was, to me, the most agreeable one that I have yet spent in this country. The greatest harmony prevailed among us, the days glided on smoothly, and the winter passed, almost imperceptibly, away.

In Daniel's Words: Archibald Norman McLeod

|

| Archibald Norman McLeod |

"Friday, September 1. In the morning, Mr. McGillis, with most of the people, left us to proceed to the Red Deer River, where they are to pass the ensuing winter. Mr. McLeod, with a number of people in one canoe, has gone to Lac Bourbon, which place lies nearly north west from this. We here take, in nets, the white fish, which are excellent."

Sunday, 12. The people destined to build a fort which is situated nearly one hundred miles to the westward of this, among the Prairies. There I shall pass the winter, with Mr. McLeod, or go and build by the side of the Hudson Bay people, who are about three leagues distant from him.—Our men shoot a few horses and ducks. Thursday, 16. We have taken a few fish out of this river, with nets. This evening, two men on horses arrived from Alexandria, by whom I received a letter from Mr. McLeod, requesting me to accompany them to that place.

This place lies in Latitude 52° north, and in 103° west Longitude. Mr. McLeod is now gone to fort Dauphine, on horse back, which lies only four day's march from this, over land; yet it is nearly two months, since I passed there in a canoe. Tuesday, 28. Mr. McLeod and company have just returned from fort Dauphine; and I am happy in meeting him, after so long a separation, and he appears to be pleased to see me, safely here. From the time that I was left at the Encampment Island until now, I have had no French, though I can read it tolerably well.

Sunday, November 30. This, being St. Andrew's day, which is a fete among the Scotch, and our Bourgeois, Mr. McLeod, belonging to that nation, the people of the fort, agreeably to the custom of the country, early in the morning, presented him with a cross, &c., and at the same time, a number of others, who were at his door, discharged a volley or two of muskets. Soon after, they were invited into the hall, where they received a reasonable dram, after which, Mr. McLeod made them a present of a sufficiency of spirits, to keep them merry during the remainder of the day, which they drank at their own house. In the evening, they were invited to dance in the hall; and during it, they received several flagons of spirits. They behaved with considerable propriety, until about eleven o'clock, when their heads had become heated, by the great quantity them became quarrelsome, as the Cana dians generally are, when intoxicated, and to high words, blows soon succeeded; and finally, two battles were fought, which put an end to this truly genteel, North Western ball.

Saturday, April 4. Swan River Fort. Here I arrived this afternoon, and have come to pass the remainder of the spring. While at Alexandria, my time passed agreeably in company with A. N. McLeod, Esq. who is a sensible man, and an agreeable companion. He appeared desirous of instructing me in what was most necessary to be known, respecting the affairs of this country; and a taste for reading I owe, in a considerable degree, to the influence of his example. These, with many other favours, which he was pleased to show me, I shall ever hold in grateful remembrance.—But now I am comparatively alone, there being no person here, able to speak a word of English; and as I have not been much in the company of those who speak the French language, I do not as yet, understand it very well. Happily for me, I have a few books; and in perusing them, I shall pass most of my leisure moments.

Friday, 15. Sent five men with a canoe, two days march up this river, for Mr. McLeod and company, as the face of the country extensively lies under water. Wednesday, 20. The water has left the fort; and with pleasure, we leave our tents, to occupy our former dwellings. This afternoon Mr. McLeod, and company, arrived, and are thus far on their way to the Grand Portage. Tuesday, 26. Yesterday, our people finished making our furs into packs, of ninety pounds weight each. Two or three of these make a load for a man, to carry across the portages. This morning, all the hands, destined to this service, embarked on board of five canoes, for Head-quarters. To Mr. McLeod, I delivered a packet of I expect to pass the ensuing summer, and to superintend the affaire of that place and of this, until the next autumn.

Mr. A. N. McLeod has a son here named Alexander, who is nearly five years of age, and whose Mother is of the tribe of the Rapid Indians. In my leisure time, I am teaching him the rudiments of the English language. The boy speaks the Sauteux and Cree fluently, for a child; and makes himself understood tolerably well, in the Assiniboin and French languages. In short, he is like most of the children of this country, blessed with a retentive memory, and learns very readily.

Sunday, 30. Yesterday, three of our people arrived from the Grand Portage, with letters from Mr. McLeod, &c, which inform me, that the above mentioned people, together with others who remained at Swan River fort, were sent off from head quarters, earlier than usual, with an assortment of goods, supposing, that we might need some articles, before the main brigade arrives.

Sunday, 27. It has snowed and rained all day. This afternoon, Mr. McLeod and company, returned from the Grand Portage, and delivered to me letters from my friends in my native land; and I am happy in being informed, that they left them blessed with good health. Self-banished, as I am, in this dreary country, and at such a distance from all I hold dear in this world, nothing beside, could give me half the satisfaction, which this intelligence affords. I also received several letters from gentlemen in different parts of the widely extended North West Country.

Thursday, 29. On the 22nd instant, Mr. McLeod, with ten of his people, arrived on horseback; and on the day following, I accompanied them to the lowef fort, where I met Mr. William Henry, a clerk. Mr. McLeod has also brought another clerk into this country, by the name of Frederick Goedike. This evening, Messrs. McLeod, Henry and myself returned, but left the people behind, whose horses are loaded with goods, for this place and Alexandria.

Wednesday, December 23. Clear and cold. On the 16th inst. I went to Alexandria, where I passed several days agreeably, in the company of Messrs. McLeod, Henry, and Goedike. We have now more snow than we had at any time the last winter. In consequence of lameness, I returned on a sledge drawn by dogs.

Thursday, 6. This morning, I received a letter from Mr. McLeod, who is at Alexandria, informing me, that a few nights since, the Assiniboins, who are noted thieves, ran away with twenty two of his horses. Many of this tribe, who reside in the large prairies, are constantly going about to steal horses. Those which they find at one fort, they will take and sell to the people of another fort. Indeed, they steal horses, not unfrequently, from their own relations. Wednesday, 12. It has snowed and rained, during the day.—On the 7th inst. I went to Alexandria, to transact business with Mr. McLeod. During this jaunt, it rained almost constantly; and on my return, in crossing this river, I drowned my horse, which cost last fall, one hundred dollars in goods, as we value them here. Monday, 17. This afternoon, Mr. McLeod and company passed this place, and are on their way to the Grand Portage. But I am to pass, if Providence permit, another summer in the interiour, and to have the superintendence of the lower fort, this place and Alexandria, residing chiefly at the latter place.

Thursday, January 27, 1803. I have just returned from Alexandria, where I passed six days, much to my satisfaction, in the company of Messrs. H. McGillies, W. Henry and F. Goedike. While there, I wrote to Messrs. McLeod, A. Henry and J. Clarke, all of Athabasca, which letters will be taken to them, by our winter express.

Wednesday, September 3. ...I have also received letters from Mr. A. N. McLeod, and Mr. J. McDonald, which inform me, that I am to pass the ensuing winter at Cumberland House, for which place, I shall leave this, a few days hence.

Tuesday, 16. White River. In the morning we left the fort, at the entrance of Lake Winnipick River, and this afternoon, Mr. A. N. McLeod and company, from Athabasca, overtook us. With this gentleman, to whom I am under many obligations, I am happy to spend an evening, after so long a separation.

Monday, 20. The snow is fast dissolving.— .. Mr. A. R. McLeod and company, have just arrived from the Encampment Island; and they bring the melancholy intelligence of the death of Mr. Andrew McKenzie, natural son of Sir Alexander McKenzie. He expired at Fort Vermillion, on the 1st inst. The death of this amiable young man, is regretted by all who knew him.

In Daniel's Words: Charles Chaboillez, François la Rocque, and the Lewis and Clarke Expedition

|

| Charles Chaboillez |

Thursday, October i. This afternoon, Mr. Francis la Rocque arrived, from Montagne a la Basse, which lies about five days' march from this, down the river. He brought me letters from several gentlemen in this country, one of which is from Mr. Charles Chaboillez, who informs me that this place will be supplied with goods, this season, by the way of the Red River, of which department he has the superintendence. As I am to pass the winter here, he desires me to accompany Mr. La Rocque, down to Montagne a la Basse, and receive such goods as will be necessary for the Indians at this post. Friday, 26. Agreeably to the instructions of Mr. Chaboillez, in company with Mr. La Rocque, and an Indian, who served as guide, I set out on the 6th instant, for Montague a la Basse. Our course was nearly south, over a plain country; and on the 9th, we reached Riviere qui Apelle, where the North West and X. Y. companies have each a fort, where we tarried all night, with Monsieur Poitras, who has charge of that post. The next morning, we continued our march, which was always in beautiful plains, until the 11th, when we arrived at the place of our destination. There I found Mr. Chaboillez, C. McKenzie, &c. The fort is well built, and beautifully situated, on a very high bank of the Red River, and overlooks the country round to a great extent, which is a perfect plain. There can be seen, at almost all seasons of the year, from the fort gate, as I am informed, buffaloes grazing, or antelopes bounding over the extensive plains, which cannot fail to render the situation highly pleasant. I spent my time there very pleasantly, during eight days, in company with the gentlemen above mentioned. At times, we would mount our horses, and ride out into the plains, and frequently try the speed of our beasts.

On the 19th, I left that enchanting abode, in company with Messrs. Chaboillez, McKenzie, &c., and the day following, arrived at Riviere qui Apelle, where we found the people, waiting our arrival. They came here by water; but at this season, canoes go up no further, on account of the shallowness of the river. The goods intended for Alexandria, therefore, must be taken from this on horse back. Accordingly, we delivered out to the people such articles as we thought necessary, and sent them 'off; and the day following, Mr. Chaboillez returned to Montagne a la Basse, and Mr. McKenzie and myself proceeded to Alexandria, where we arrived this afternoon, after having made a pleasant jaunt of twenty one days. Here I shall pass the winter, having with me Mr. Goedike, two interpreters, twenty labouring men, fourteen women and sixteen children.

Saturday, November 24. Some people have just arrived from Montagne a la Basse, with a letter from Mr. Chaboillez, who informs me, that two Captains, Clarke and Lewis, with one hundred and eighty soldiers, have arrived at the Mandan Village on the Missouri River, which place is situated about three days' march distant from the residence of Mr. Chaboillez. They have invited Mr. Chaboillez to visit them. It is said, that on their arrival, they hoisted the American flag, and informed the Natives that their object was not to trade, but merely to ex plore the country; and -that as soon as the navigation shall open, they design to continue their route across the Rocky Mountain, and thence descend to the Pacific Ocean. They made the Natives a few small presents, and repaired their guns, axes, &c., gratis. Mr. Chaboillez writes, that they behave honourably toward his people, who are there to trade with the Natives.

Wednesday, April 10. On the 24th ult. I set out on horse back, accompanied by one man, for Montagne a la Basse. When we arrived there, we were not a little surprised to find the fort gates shut, and about eighty tents of Crees and Assiniboins encamped in a hostile manner, around it, and threatening to massacre all the white people in it. They, in a menacing manner, threw balls over the palisades^ and told our people to gather them up, declaring that they would probably have use for them in the course of a few days. After having passed several days there, I set out to return home. Just as I had gotten out of the fort gate, three vil lainous Indians approached me, and one of them seized my horse by the bridle and stopped him, saying, that the beast belonged to him, and that he would take him from me. I told him that he had disposed of him to Mr. Chaboillez, who had charge of the post; and that of this gentleman, I had purchased him, and that I had no concern with the matter, which was wholly between him and Mr. Chaboillez. Perceiving, however, that he was determined not to let go of the bridle, I gave him a smart blow on his hand, with the butt end of my whip, which consisted of a deer's horn, and instantly striking my horse, I caused him to spring forward, and leave the Indian behind. Finding myself thus clear of this fellow, I continued my rout; but he with one of his companions, followed us nearly half of the day, if not longer. After this length of time we saw no more of them. Apprehensive, however, that they might fall upon us in our encampment at night, and steal our horses, and probably massacre us, after it became dark, we went a little out of the path, and laid ourselves down; but we dared not make a fire, lest the light or the smoke should discover the place where we were.

While at Montague a la Basse, Mr. Chaboillez, induced me to consent to undertake a long and arduous tour of discovery. I am to leave that place, about the beginning of June, accompanied by six or seven Canadians, and by two or three Indians. The first place, at which we shall stop, will be the Mandan Village, on the Missouri River. Thence, we shall steer our course towards the Rocky Mountain, accompanied by a number of the Mandan Indians, who proceed in that direction every spring, to meet and trade with another tribe of Indians, who reside on the other side of the Rocky Mountain. It is expected that we shall return from our excursion, in the month of November next. [This journey, I never undertook; for soon after the plan of it was settled, my health became so much impaired, that I was under the necessity of proceeding to Head Quarters, to procure medical assistance. A Mr. La Rocque attempted to make this tour; but went no farther than the Mandan Village.]

See LaRoque's Journal of a Voyage to the Rocky Mountains

Monday, 27. Riviere a la Souris, or Mouse River. This is about fifty miles from Montagne a la Basse. Here are three establishments, formed severally by the North West, X. Y. and Hudson Bay companies. Last evening, Mr. Chaboillez invited the people of the other two forts to a dance; and we had a real North West country ball. When three fourths of the people had drunk so much, as to be incapable of walking straightly, the other fourth thought it time to put an end to the ball, or rather bawl. This morning, we were invited to breakfast at the Hudson Bay House, with a Mr. McKay, and in the evening to a dance. This, however, ended more decently, than the one of the preceding evening.

Monday, August 3. First long Portage in the Nipigon Road. We yesterday, separated from Messrs. Chaboillez and Leith, who have gone to winter at the Pic and Michipcotton; and to day, we left Lake Superiour, and have come up a small river.

Daughters of the Country

If we "unpack" the image of the voyageur into its essential qualities, we can find women to match virtually every criterion of the definition. In the sheer strength category, the Chipwyan women of Alexander Henry's journals could pull a loaded York boat of furs on rollers. For endurance, we have Métis hero Louis Riel's grandmother, Marie-Anne Lajimodière, who was thrown and dragged from her horse in her ninth month, and gave birth safely the next day. Lisette herself may be the record-holder for distance at speed: four thousand miles in eleven weeks.

Experienced voyageurs became guides, sharing their extensive knowledge of the canoe country. The Chipwyan Thanadelthur and the Shoshone Sacajawea, both "country wives" of fur traders, have entered the historical record as "guide and interpreter," as did many nameless women along the routes. David Thompson's Métis wife Charlotte, and their children, traveled with him on his famous mapping expeditions to the Rockies.

Were women restricted to "blue-collar" positions in the fur trade? Hardly. The Grignon sisters of Wisconsin had become two of the largest landowners in Green Bay by the 1840s. Juliette Kinzie, wife of an Indian agent, had the wherewithal to bring her piano with her in the canoe to Portage, Wisconsin. Arguably the most famous woman of the fur trade, Frances Anne Hopkins, was the bourgeoise wife of Governor Simpson, giving her name to Fort Frances, Ontario.

Madeleine LaFramboise of Mackinac spoke six languages and, when widowed, took over her husband's business so successfully that John Jacob Astor made her one of his agents. (Mme. La Framboise also had at least three husbands, giving her a running in the six-wives category, though there is no mention of running dogs.)

Native and Métis women were cultural voyageurs into the advancing European societies through their relationships with traders, their community and the land. And the enduring values of the voyageur's strong esprit de corps blend a respectful love of wilderness and freedom with the camaraderie of campfire, song, and paddle.

Walking In Her Moccasins

Any modern canoeist longs for the era of the voyageurs. The landscape itself evokes them. When the mist rises on Saganaga Lake, you can almost see the stern of the great canoes vanishing ahead of you in the fog. In the silent dip of the paddle, there is an echo of the rhythm of a song long vanished, yet recognizable as a heartbeat. In the call of wolf and loon, you know you can hear the voyageurs singing.

We all talk to the past. Women who value the voyageur mystique have a particular and dual challenge in seeking to reenact it. Modern, culturally European "woodswomen" identify with both halves of the fur trade split: we are white like the men and women like the natives. When we succeed in achieving this dual vision, it pops the fur trade into stereo.

The story of Daniel and Lisette Harmon has a unique ability to fuse the dualities that have been used for so long to define not only the fur trade era, but North American history itself. Strong, adventurous women long to put ourselves in the picture, to feel personally connected to a history in which we have long been taught we are invisible-or identified as male. When both men and women can identify with both Lewis and Clark and with Sacajawea, with both Lisette and Daniel Harmon, we will have gained new dimensions to the history of our continent and our place upon it.

We choose living history as a means to walk a mile in another's moccasins. I began Lisette's journey in 1988 with a passion for paddling and singing, those twin loves of the voyageur. Lisette has since given me a second language, a second country, three national awards, a major book and a CD, a passport to the past, insight into those not of my race or gender, and an enduring fascination with our great continent and its history of adventurous women. Lisette Duval has become my hero, and I am proud to walk in her moccasins.

A Legacy of Endurance

Lisette was a woman of endurance. She made an epic transcontinental journey while pregnant and nursing a newborn, as well as caring for two young daughters throughout the canoe trip. She bore fourteen children, ten surviving infancy, and outlived all but one. She was a devoted and beloved mother, and a "fair partner" all her days.

Lisette's patient, listening ear and keen eye for detail live on in her work. Harmon's journal, edited by the Rev. Daniel Haskell, includes a Cree dictionary that was made correct "by making the nice distinctions in the sound of the words, as derived from her repeated pronunciation of them."

Lisette's one surviving artifact is a quillworked leather shot bag in the Bennington Museum, acclaimed by art historians and anthropologists as one of the finest surviving examples of its genre. The stitches are tiny and close-set, the vegetable dyes rich and bright, the leather fine and supple, and the design exquisite. One can only imagine how many long summer days on canoe trips, and harsh winter nights from the Rockies to Vermont and MontrŽal, found her sewing by the fire, attentive to her task.

The Vermont Years

"I have at length arrived at headquarters. In coming from New Caledonia to this place, which is a distance of at least three thousand miles, nothing uncommon has occurred."

Nothing uncommon indeed, in making a transcontinental wilderness journey with a nine-months' pregnant woman and two small children. Nothing uncommon, in a marriage performed two days before a birth. After the free and easy days of the fur trade, what would soon seem uncommon to the Harmons was the life ahead of them.

Lisette was twenty-eight when she arrived in whitewashed Yankee Vermont. Half her life had been spent with Daniel, who was as much father as husband to her. She would spend the next twenty-four years in the young United States, raising ten children often alone, when Daniel took short assignments with the NorthWest Company.

Daniel's brothers Argalus and Calvin Harmon were comfortable Vergennes farmers turned land speculators. In 1820, they purchased a remote township in Vermont's Northeast Kingdom, a burgeoning wilderness of some 300 families. An experienced trader with some capital on hand, such as retirement pay from the NWC, was just the thing to grow the town.

Daniel soon found himself developing the first sawmill for Harmonville, later renamed Coventry. The mill on the Black River swiftly turned forests into farmland and timber into lumber, and the Harmon brothers were ardent in their land clearing efforts. Deacons of the church, they also took a dim view of drinking.

"Harmon, being much opposed to the use of alcohol and having given the land for the town common, set the penalty for drunkenness at the clearing of one stump from the common. This proved to be more effective at clearing land than at preventing drunkenness. Thereafter, one pint of rum was justly considered the fair price of pulling out one stump." (Vermont Historical Gazetteer)

Little is known of the Harmons' Vermont years, as the Coventry records perished in a fire in the mid-1960s. A contemporary journal, since lost, apparently makes some reference to the death of "the widow Harmon," indicating that Daniel's mother Lucretia lived with her sons after their father's death. Daniel eventually built a frame house for the growing family, as Lisette bore six more children in Coventry. Almira Amelia was born May 16, 1821; Henry Norman on March 13, 1825; Frederick Mortimer on January 4, 1828; Stephen on July 28, 1831; Susan Elizabeth on March 29, 1833; and Abby Maria on July 27, 1838.

In 1843, the Harmon family moved again, returning to Montreal. Recent research in Montreal and New Hampshire archives has unearthed a surprising reason for the move, which has long been inexplicable to Harmon scholars.

The Harmons' eldest daughter Polly had married a blacksmith from East Haverhill, NH by the name of Calvin Ladd. It seems that in 1842, Calvin Ladd purchased land on the island of Montreal from a well-known Montreal merchant Pascal Persillier. His son, Pascal Persillier-Lachapelle, had long feared that British merchants were overpowering (French) Canadian commerce. In 1837, Persillier had proposed a motion in the Saint Lawrence Patriots assembly to "liberalize commercial exchange" with the United States so that together they might "seize the economic and political jugular" of Great Britain. With his father, Persillier was elected a permanent member of the Patriot committee of Montréal.

Who better for the Montrealers to recruit for their patriotic purposes than the merchant son-in-law of a prominent NorthWest Company trader, whose wife was bilingual in French? Calvin Ladd had worked at the Fairbanks Scale Company in St. Johnsbury, Vermont, and was aware of the potential of the growing Industrial Revolution. While there is no direct evidence linking these events to the Harmon's move, it is certain that the Daniel Harmon family departed Coventry in the late winter of 1843 for Sault-au-Récollet, Quebec on the Rivière Des Prairies on l'Ile de Montréal (incorporated into the City in 1906).

The move was to be the death of Daniel. There is a record of an erysipelas (swine fever) epidemic in Coventry that winter, and its symptoms can mimic those of scarlet fever in humans. Frederick Mortimer, aged 15, was the first to die in March of 1843, perhaps weakened by a long winter journey on the frozen rivers that made travel more possible in the era before roads. Daniel also died in March, barely 65 years old; on May 26 he was followed by daughter Sally, now 26.

Polly was now the only one left who remembered Lisette's homeland. Her husband Calvin sued on Lisette's behalf for custody of Daniel's estate and the remaining children, and family records from this point bear the name of Ladd. Harmon descendant Joseph Betz notes that on the 22nd of February, 1861, Calvin Ladd's foundry and machine shops were destroyed by fire, and he sold out what property remained at Sault-au-Recollet and returned to the States. He accepted a position in the chief engineer's office at the Brooklyn Navy Yard. Polly died September 27, 1861 in Montreal, and Calvin married Charlotte E. Welsh on November 10, 1864 in Brooklyn, NY.

Lisette lived on in Montreal until February 14, 1862, the age of 72, when she was buried in Mount Royal Cemetery. Her life began in the year of the division of Upper and Lower Canada (b. 1791), and spanned the continent and the century to end on the eve of the American Civil War (d. 1862) and Canadian Confederation (1867). Her youngest daughter Abby Maria (who died a suicide by drowning in Ottawa) was buried in her mother's grave. The stone to both Harmons in Mount Royal Cemetery was probably a gift of Abby Maria's friends.

1819: "If She Is Willing to Continue the Connection"

On February 28, 1819, Daniel wrote in his journal of his decision to return to Vermont. Faced with the choice made by so many men of his era, he could not follow through on his original intention:

"to place her into the hands of some good honest Man, with whom she can pass the remainder of her Days in this Country much more agreeably, than it would be possible for her to do, were she to be taken down into the civilized world, where she would be a stranger to the people, their manners, customs & Language."

It was her choice to make, and they would face the strangers together as man and wife.

"...I design to make her regularly my wife by a formal marriage...Having lived with this woman as my wife...and having children by her, I consider that I am under a moral obligation not to dissolve the connexion, if she is willing to continue it. The union which has been formed between us, in the providence of God, has not only been cemented by a long and mutual performance of kind offices, but also by a more sacred consideration...

"We have wept together over the departure of several children, and especially over the death of our beloved son George. We have children still living who are equally dear to both of us. How could I spend my days in the civilized world and leave my beloved children in the wilderness? How could I tear them from a mother's love and leave her to mourn over their absence to the day of her death? How could I think of her in such circumstances without anguish?"

Lisette and Daniel achieved Harmon's stated ideal of a relationship (1800), to "live in harmony together." Their partnership was lifelong, devoted, and based on mutual respect. Their relationship was a practice of cross-cultural exchange. Each gained entry into the other's milieu, as well as a dynastic union which satisfied both Harmon's deep need for family connection, and the custom (which he often observed among Indian women) of cheerfully choosing large families. Harmon wrote "I cannot conceive it right for a man and woman to cohabit when they do not agree," and clearly they did agree. Lisette was evidently "willing to continue the connexion," for his lifetime and for the remaining 29 years of hers.

"to place her into the hands of some good honest Man, with whom she can pass the remainder of her Days in this Country much more agreeably, than it would be possible for her to do, were she to be taken down into the civilized world, where she would be a stranger to the people, their manners, customs & Language."

It was her choice to make, and they would face the strangers together as man and wife.

"...I design to make her regularly my wife by a formal marriage...Having lived with this woman as my wife...and having children by her, I consider that I am under a moral obligation not to dissolve the connexion, if she is willing to continue it. The union which has been formed between us, in the providence of God, has not only been cemented by a long and mutual performance of kind offices, but also by a more sacred consideration...

"We have wept together over the departure of several children, and especially over the death of our beloved son George. We have children still living who are equally dear to both of us. How could I spend my days in the civilized world and leave my beloved children in the wilderness? How could I tear them from a mother's love and leave her to mourn over their absence to the day of her death? How could I think of her in such circumstances without anguish?"

Lisette and Daniel achieved Harmon's stated ideal of a relationship (1800), to "live in harmony together." Their partnership was lifelong, devoted, and based on mutual respect. Their relationship was a practice of cross-cultural exchange. Each gained entry into the other's milieu, as well as a dynastic union which satisfied both Harmon's deep need for family connection, and the custom (which he often observed among Indian women) of cheerfully choosing large families. Harmon wrote "I cannot conceive it right for a man and woman to cohabit when they do not agree," and clearly they did agree. Lisette was evidently "willing to continue the connexion," for his lifetime and for the remaining 29 years of hers.

Sixteen Years in the Indian Country: an Overview

In 1800, Daniel's first assignment was as a clerk on the "voyageur's highway" from Montreal to Grand Portage, and thence to Fort Alexandria, Saskatchewan. He worked a total of five years in the Swan River Department, as central Saskatchewan was then known, with sojourns (assignments, or tours of duty) at Fort Alexandria, Bird Mountain, and Lac la Pêche.

From 1805 to 1807, Daniel worked on the Saskatchewan River at New Fort, South Branch House, and Cumberland House. On October 10, 1805, he was introduced to the young woman who would become his wife. At the tender age of 14, Lisette was, according to Daniel's journal, "a fair Partner of a mild disposition and even-tempered." Nothing is known of her origin or that of her tribe, and she was long thought to be a Snake Indian from the Kootenays. "Snare" has long been considered a misspelling in Harmon's original journal; recent scholars have speculated that the "Snare" people do exist, and are now the Secwepemec band of the North Thompson River, BC, but in 1997, Secwepemec band leaders were unable to confirm this.

1810: Rocky Mountain District

A great remove to New Caledonia in 1810 took the Harmons into the Rocky Mountain region for a decade. Three sojourns at Stuarts Lake led to Daniel's posting as factor at a new fort at Fraser's Lake, British Columbia, just across the continental divide. Fraser Lake fort was founded by Daniel's fellow Bennington native Simon Fraser , the North West Company adventurer famed for his discovery and descent of the Fraser River to Vancouver.